Why your tests aren’t scientific

I read a lot of articles about A/B tests and I keep being surprised by the differences in testing that I see. I think it’s safe to say: most conversion rate optimization testing is not scientific. It will simply take up too much space to explain what I mean exactly by being scientific, but I’ll publish a post on that next week, together with Marieke.

I’ll be very blunt throughout this post, but don’t get me wrong. A/B testing is an amazing way to control for a lot of things normal scientific experiments wouldn’t be able to control for. It’s just that most people make interpretations and draw conclusions from the results of these A/B tests, that make no sense whatsoever.

Not enough data

The first one is rather simple, but still a more common mistake than I could ever have imagined. When running an A/B test, or any kind of test for that matter, you need enough data to actually be able to conclude anything. What people seem to be forgetting is that A/B tests are based on samples. When I use Google, samples will be defined as follows:

a small part or quantity intended to show what the whole is like

For A/B testing on websites, this means you take a small part of your site’s visitors, and start to generalize from that. So obviously, your sample needs to be big enough to actually draw meaningful conclusions from it. Because it’s impossible to distinguish any differences if your sample isn’t big enough.

Having too small a sample would be a problem with your Power. The power is a scientific term, which means the probability that your hypothesis is actually true. It depends on a number of things, but increasing your sample size is the easiest way to make your power higher.

Run tests full weeks

However, your sample size and power can be through the roof, it all doesn’t matter if your sample isn’t representative. What this means is that your sample needs to logically resemble all your visitors. By doing this, you’ll be able to generalize your findings to your entire population of visitors.

And this is another issue I’ve encountered several times: a lot of people never leave their tests running for full weeks (of 7 days). I’ve already said in one of my earlier posts, that people’s online behavior differs every day. So if you don’t run your tests full weeks, you will have tested some days more often than others. And this will make it harder to generalize from your sample to your entire population. It’s just another variable you’d have to correct for, while preventing it is so easy.

Comparisons

The duration of your tests becomes even more important when you’re comparing two variations against each other. If you’re not using a multivariate test, but want to test using multiple consecutive A/B tests, you need to test these variations for the same amount of time. I don’t care how much traffic you’ve gotten on each variation; your comparison is going to be distorted if you don’t.

I came across a relatively old post by ContentVerve last week (which is sadly no longer online), because someone mentioned it in Michiel’s last post. Now, first of all, they’re not running their tests full weeks. There’s just no excuse for that, especially if you’re going to compare tests. On top of that, they are actually comparing tests, but they’re not running their tests evenly long. Their tests ran for 9, 12, 12 and 15 days. I’m not saying evening this would change the result. All I’m saying is that it’s not scientific. At all.

Now I’m not against ContentVerve, and even this post makes a few interesting points. But I don’t trust their data or tests. There’s one graph in there that specifically worked me up:

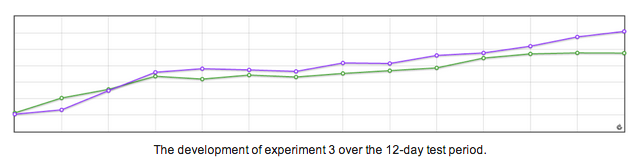

Now this is the picture they give the readers, right after they said this was the winning variation with a 19.47% increase in signups. To be honest, all I’m seeing is two very similar variations, of which one has had a peak for 2 days. After that peak, they stopped the test. By just looking at this graph, you have to ask yourself: is this effect we’ve found really the effect of our variation?

Data pollution

That last question is always a hard question to answer. The trouble of running tests on a website, especially big sites, is that there are a lot of things “polluting” your data. There are things going on on your website; you’re changing and tweaking things, you’re blogging, you’re being active on social media. These are all things that can and will influence your data. You’re getting more visitors, maybe even more visitors willing to subscribe or buy something.

We’ll just have to live with this, obviously, but it’s still very important to know and understand it. To get ‘clean’ results you’d have to run your test for a good few weeks at least, and don’t do anything that could directly or indirectly influence your data. For anyone running a business, this is next to impossible.

So don’t fool yourself. Don’t ever think the results of your tests are actual facts. And this is even more true if your results just happened to spike on 2 consecutive days.

Interpretations

One of the things that even angered me somewhat is the following part of the ContentVerve article:

My hypothesis is that – although the messaging revolves around assuring prospects that they won’t be spammed – the word spam itself give rise to anxiety in the mind of the prospects. Therefore, the word should be avoided in close proximity to the form.

This is simply impossible. A hypothesis is defined, once again by Google, as “a supposition or proposed explanation made on the basis of limited evidence as a starting point for further investigation.” The hypothesis by ContentVerve is in no way made on the basis of any evidence. Let alone the fact he won’t ever pursue further investigation into the matter. With all due respect, this isn’t a hypothesis: it’s a brainfart. And to say you should avoid doing anything based on a brainfart is, well, silly.

This is a very common mistake among conversion rate optimizers. I joined this webinar by Chris Goward, in which he said (14 minutes in), and I quote:

“It turns out that in the wrong context, those step indicators can actually create anxiety, you know, when it’s a minimal investment transaction, people may not understand why they need to go through three steps just to sign in.”

And then I left. This is even worse, because he’s not even calling it a hypothesis. He’s calling it fact. People are just too keen on getting a behavioural explanation and label it. I’m a behavioural scientist, and let me tell you; in studies conducted purely online, this is just impossible.

So keep to your game and don’t start talking about things you know next to nothing about. I’ve actually learned for this kind of stuff and even I’m not kidding myself I understand these processes. You can’t generalize the findings of your test beyond anything of what your test is measuring. You just can’t know, unless you have a neuroscience lab in your backyard.

Significance is not significant

Here’s what I fear the people at ContentVerve have done as well: they left their test running until their tool said the difference was ‘significant’. Simply put: if the conversions of their test variation would have dropped on day 13, their result would no longer be significant. This shows how dangerous it can be to test just until something is significant.

These conversion tools are aptly called ‘tools’. You can compare them to a hammer; you’ll use the hammer to get some nails in a piece of wood, but you won’t actually have the hammer do all the work for you, right? You still want the control, to be sure the nails will be hit as deeply as you want, and on the spot that you want. It’s the same with conversion tools; they’re tools you can use to reach a desired outcome, but you shouldn’t let yourself be led by them.

I can hear you think right now: “Then why is it actually working for me? I did make more money/get more subscriptions after the test!” Sure, it can work. You might even make more money from it. But the fact of the matter is, in the long run, your tests will be far more valuable if you do them scientifically. You’ll be able to predict more and with more precision. And your generalizations will actually make sense.

Conclusion

It all boils down to these simple and actionable points:

- Have a decent Power, among others by running your tests for at least a week (preferably much more);

- Make your sample representative, among others by running your tests full weeks;

- Only compare tests that have the same duration;

- Don’t think your test gives you any grounds to ‘explain’ the results with psychological processes;

- Check your significance calculations.

So please, make your testing a science. Conversion rate optimization isn’t just some random testing, it’s a science. A science that can lead to (increased) viability for your company. Or do you disagree?

Discussion (33)